Humpback Whale Mother & Calf

Humpback Whale Mother & Calf

Humpback whale calves are small in comparison to their mother. After much searching back and forth amongst the islands we have found a mother a calf. The calf is small, playful and inquisitive of anything new to its surrounding environment. We watch as the calf, which is not more than a week old, attempt to breach beside its mother. The technique has not yet been learned correctly and the small whale tires quickly after several failed attempts.

LEFT: Baby humpback whale keeps close to mother as we photograph the couple.

Quietly we slip into the water and float towards the mother and calf; we are conscious that our presence may disturb the  couple so we keep together as a group of four. Mother doesn’t appear to be concerned and her eye is barely open, a sign that she is not overly stressed, as such we swim a little closer. The youngster is behind mother and well protected. We had noted earlier when on the boat, that the mother would always try and position herself between us and her baby.

couple so we keep together as a group of four. Mother doesn’t appear to be concerned and her eye is barely open, a sign that she is not overly stressed, as such we swim a little closer. The youngster is behind mother and well protected. We had noted earlier when on the boat, that the mother would always try and position herself between us and her baby.

LEFT: Female Humpback Whale pivots and swims in our direction to manouer between us and the yougster.

We couldn’t see the baby although we knew it was on the far side of the mother whale, then we watched as the baby nosed under the head of mother looking at us inquisitively. Baby , apparently curious then swam out from behind the protection of mother and swam briefly in our direction. Mother, concerned at her youngster’s obvious lack of caution, pivoted her body toward us and slowly swam toward and past us with her calf swimming alongside.

Although the interaction between us and the two whales was not lengthy, it was long enough to allow us to capture a few frames which show the strong bonding and parental obligation of the mother whale towards its newborn.

The biological investment in a whale’s calf, like many mammals is high. A female whale will have a gestation period of 12 months and after birth, the newborn calf will spend a year with its mother and accompany her south to the feeding grounds in Antarctica. Until it is large enough and adequately proficient at feeding on krill, the baby whale will be sustained on an exceptionally rich formula of whale milk. The milk is saturated in high protein fats (45-60% fat) that allows the youngster to build up the thick layer of blubber required for to survive in the colder waters of Antarctica.

Distinctive Colour & Tonal Variance

It was interesting to note that each calf had a slightly different colour and pattern of counter shading. The colour of one calf was a very deep mottled black with a high contrast line between the white of its belly and its flank. Its pectoral fins were jet black – both dorsally and ventrally. In comparison, another calf I observed was almost grey in colour with very little tonal difference between its flank and white belly; watching this calf swim, it looked much paler than others I had seen. The pectoral fins on this youngster were grey dorsally with white undersides. I was to learn that each pattern is distinctive to each individual and can often be used as method of identification, similar to the tell tail signature of various patterns on tail flutes.

Shark Watch

Shark Watch

Whales are often accompanied by dolphins, remora fish and sharks. The sharks hang around female whales awaiting the birth; hopefully then they may have a chance to either feed on the placenta (after birth) or feed upon a new born calf. On all our dives, care was maintained to watch for tiger and oceanic white tip sharks, these two species being the most common to escort whales in this area. In 2009, several tiger sharks were observed feeding on a dead whale calf that had been still born. Although we were keen to see the tiger sharks, we realized that in all probability the chance was minimal.

LEFT: Humpback Whale and calf.

Humpback Whale Fact Sheet

Latin Name: - Megaptera novaeangliae

Conservation Status: - Vulnerable

Distribution: - Worldwide

Length: - 13 – 15 m (43 - 49 feet)

Weight: - 22680 – 36287 kg (25 – 40 tons)

Life Expectancy: - around 77 years

Wednesday, September 29, 2010 at 11:44AM

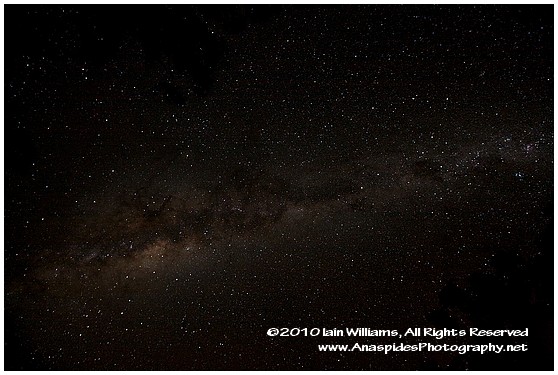

Wednesday, September 29, 2010 at 11:44AM  Stars & Night Sky

Stars & Night Sky